Frances Wolseley:

Gardener, activist, aristocrat

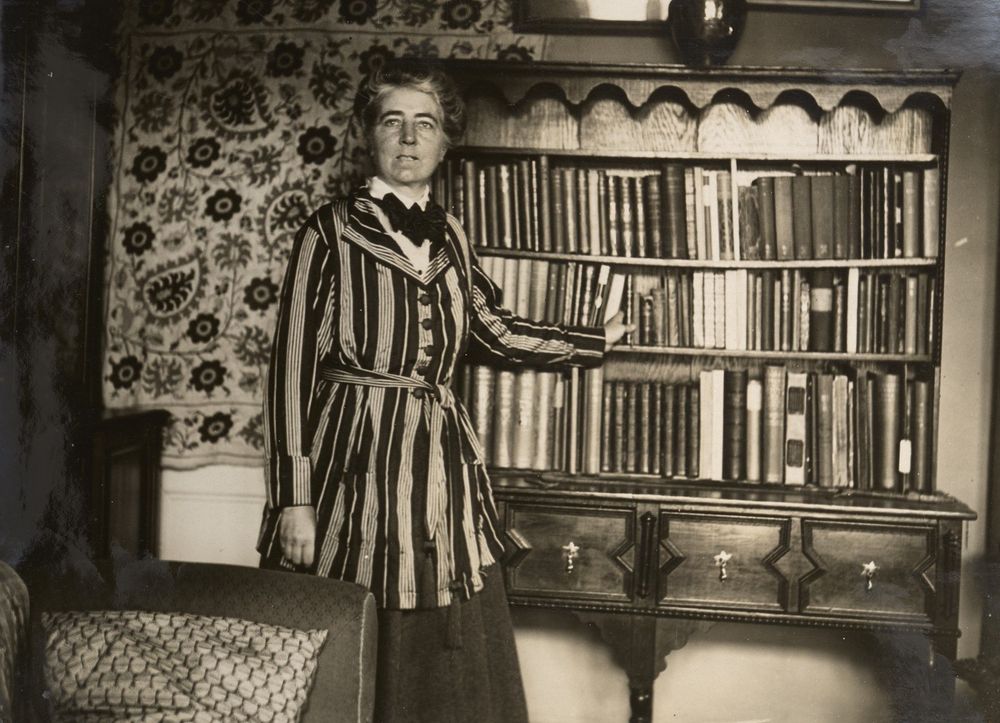

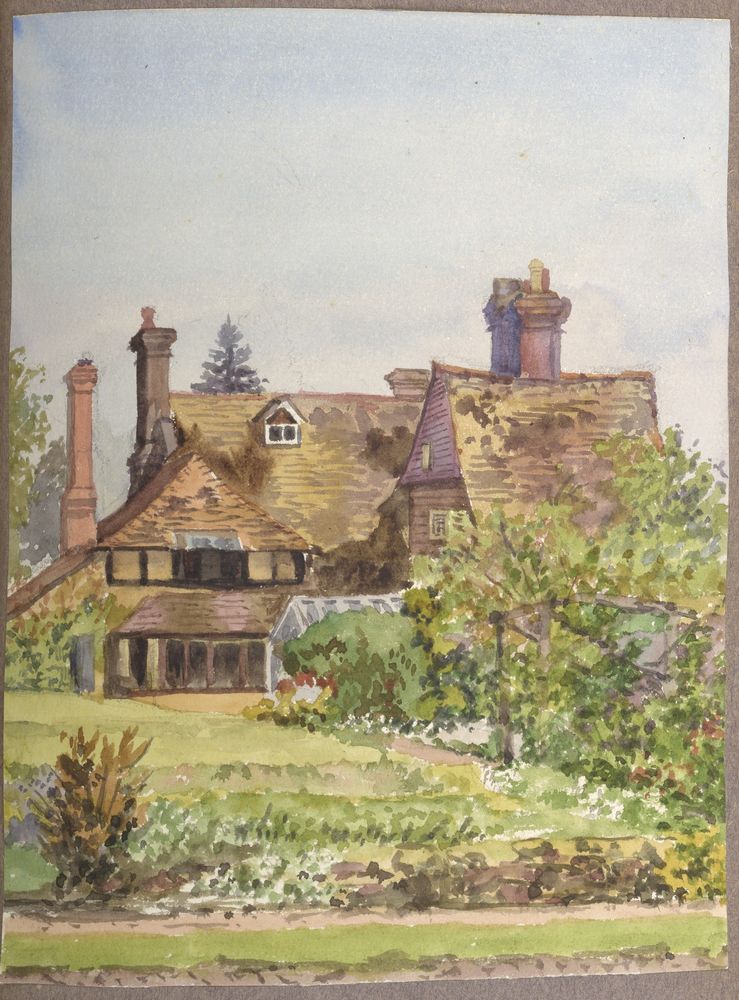

Viscountess Frances Garnet Wolseley at her home, Massetts Place, in 1922. Source: Brighton & Hove Libraries

From aristocrat to activist

Viscountess Frances Garnet Wolseley was born into privilege and bred for society.

But she chose her own path, carving out a career and lifestyle that ultimately saw her pay a high price.

As an author, garden designer, educator and organiser she became a strong supporter of women’s ability to pursue horticulture as a career.

Her decision not to marry, and instead share her life with women, means that today she is also celebrated as a queer icon.

Hove Library, part of Brighton & Hove Libraries, houses a collection that helps tell the story of her life.

Early life

Frances Wolseley was born in 1872. Her father, Field-Marshal Viscount Garnet Wolseley, would later become Commander-in-Chief of the British Army.

Her mother, Lady Louisa Wolseley, cared for Frances – who was their only child – for long periods when her husband was away with the army.

Because of their strong connections to high society, Frances grew up meeting important people.

She went on holidays with the Prince of Wales (who later became King Edward VII), and had a poem written for her by Alfred Austin, a future poet laureate. In 1885 she was introduced to Queen Victoria.

Some people think Field-Marshal Viscount Garnet Wolseley was the person who inspired the Gilbert & Sullivan song I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major-General.

You can see a statue of him today on Horse Guard’s Parade in London.

Blossoming ambition

In 1891, after being privately-educated and prepared for high society by her parents, Frances had her first social season. For several years, her mother would go with her to events, hoping to find her a suitable husband.

By this time, Frances had become interested in gardening.

When her family moved to Glynde village in East Sussex, this interest grew into a strong desire to teach women about working in gardening.

This passion would shape her whole life and career, but it would also cause problems between her and her parents.

A move for independence

After many years of attending social events, at the age of thirty Frances began offering courses in gardening and garden design for the daughters of local families.

A couple of years later, her parents decided to move to France. Frances made a bold choice to stay in England. Her parents rented out the family home, thinking Frances would join them in Europe.

However, after raising money from friends, Frances rented the greenhouse on her parents’ property from the new tenants. She used it to teach fruit cultivation to her growing number of students.

Her parents were furious. At that time, as an unmarried lady, Frances was expected to devote her life to looking after them. It was the start of a disagreement that would last many years.

Glynde School for Lady Gardeners

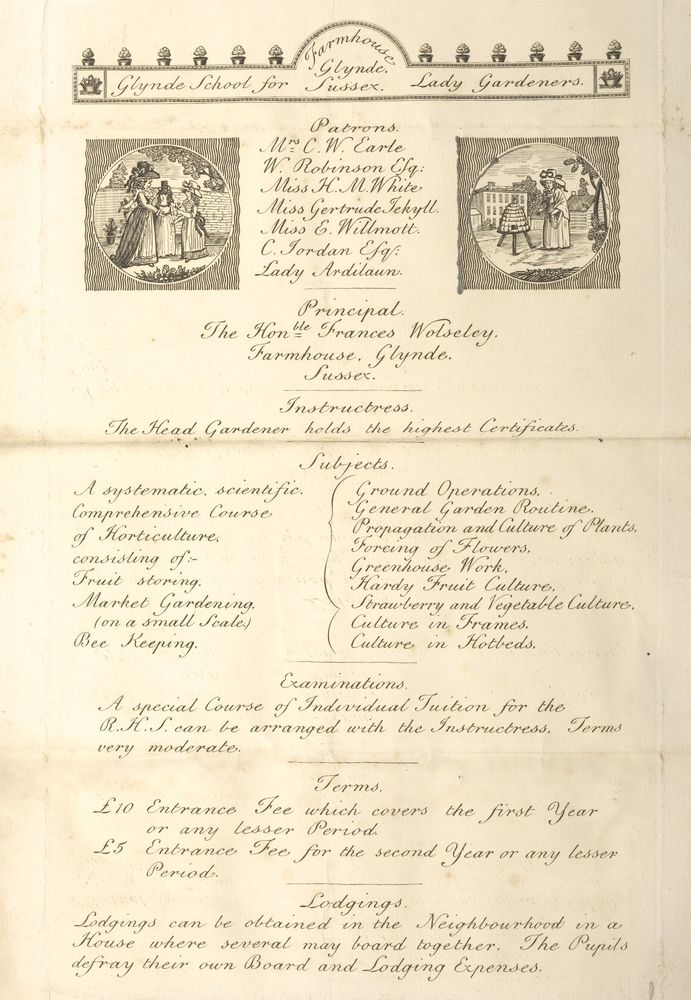

By 1906, Frances Wolseley's gardening lessons had grown and were officially named the Glynde College, or School, for Lady Gardeners.

With help from friends, she was now independent from her parents. She decided to move the college to a place with an interesting name: Ragged Lands.

Originally a field for corn and barley—and with no trees or vegetation—Frances saw its potential, building a cottage on the site and moving the college there.

By sharing her home with the college's Head Gardener, Miss Turner, it seemed she no longer felt the need to hide that she preferred the company of women.

With a large garden of five acres for teaching, the college's lessons grew into a two-year course for ladies.

But only ladies made of the right stuff...

Students, now issued uniforms, at the expanded college on Ragged Lands. The lady holding the bell on the right is Elsa More, who would take over day-to-day running of the school. Source: Brighton & Hove Libraries

Life at Glynde College

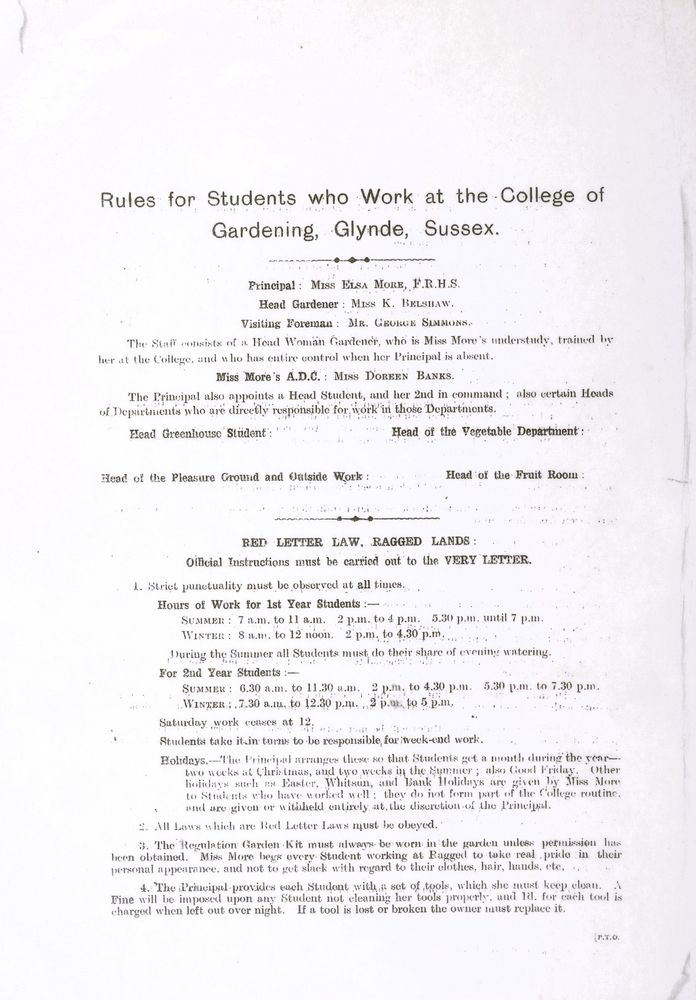

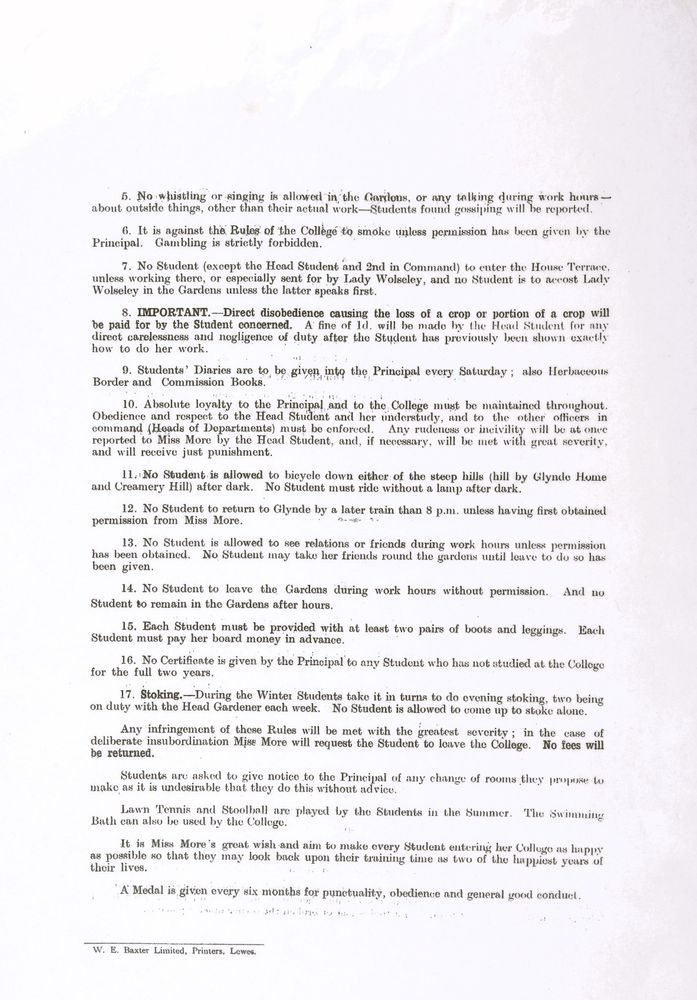

The influence of Frances’s parents loomed large at Glynde College. This was a school run like an army unit.

Students had to wear uniforms, their work was checked very carefully, and there was a long list of strict rules. Many students quickly learned that this was not a place where they could be lazy.

Because of how she was brought up, Frances had high standards, but she also had unfair ideas about people. She believed women from towns and cities were not good workers.

And she thought 'breeding' (meaning a person's family background) was very important. She felt that people from a lower class were not right for her college.

Explore Glynde College

The items in this gallery, from the Wolseley Collection at Hove Library, give an interesting look into what life was like at Glynde College. We've added clickable points on the pictures to give you more information.

Check out the long list of rules students needed to follow, and the uniform they were expected to wear.

You can also learn more about the Principal who took over from Frances Wolseley, and some of the challenges she faced.

How do you think you would have done at Glynde College?

High standards, harsh appraisals

A student register (a list of students) from the Glynde School for Lady Gardeners helps us understand the standards Frances Wolseley set and her senior staff made sure were followed.

Here are some parts from it, showing how some students who didn't do well were described (names are not included)...

A perpetual talker. Does things badly because she thinks she knows everything... Is rather a nuisance all round.

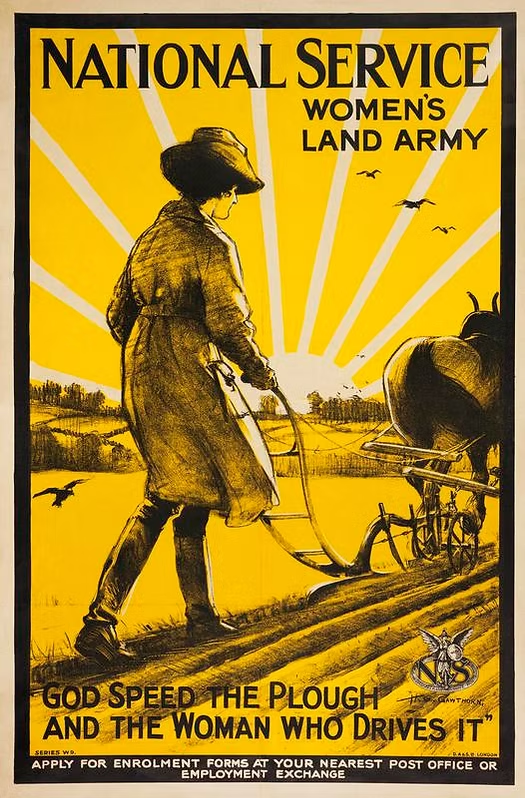

While more commonly associated with World War Two, the Women's Land Army was formed during World War One. Source: Art.IWM PST 5996, 1917

Wartime organiser

By the time World War One started in 1914, Frances Wolseley had become Viscountess Wolseley. A special agreement meant she could inherit the title when her father died.

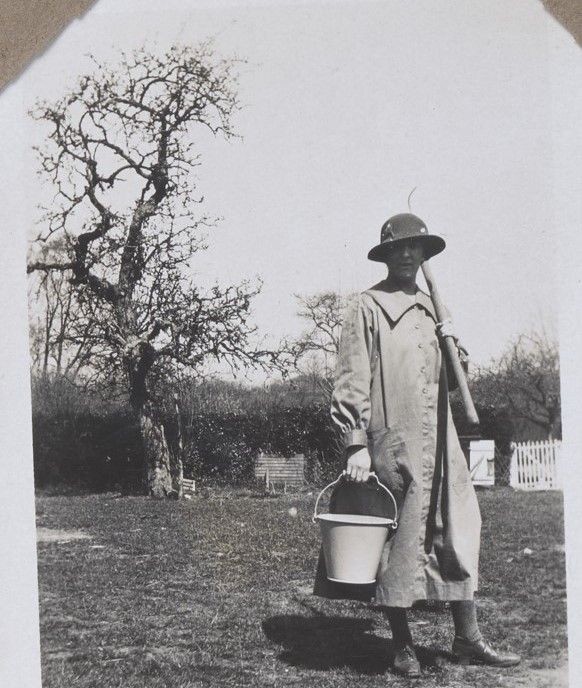

Feeling tired from the pressures of running the college, she passed its leadership to one of her students, Elsa More. The Viscountess then focused her energy on promoting how useful women could be in producing food in the absence of men who had gone off to war.

Because of this, the Government's Food Production Department asked her to organise women in East Sussex to work on farms. Germany's plan to disrupt Britain's food imports meant the country was at risk of starvation.

The British Government took over every unused piece of land so food could be grown. When the Women's Land Army was created in 1917, about 233,000 women were working in jobs connected to farming.

1918 saw the largest harvest in Britain's history, and the end of the war.

In his memoirs, Prime Minister Lloyd George wrote: "The food question ultimately decided the issue of this war."

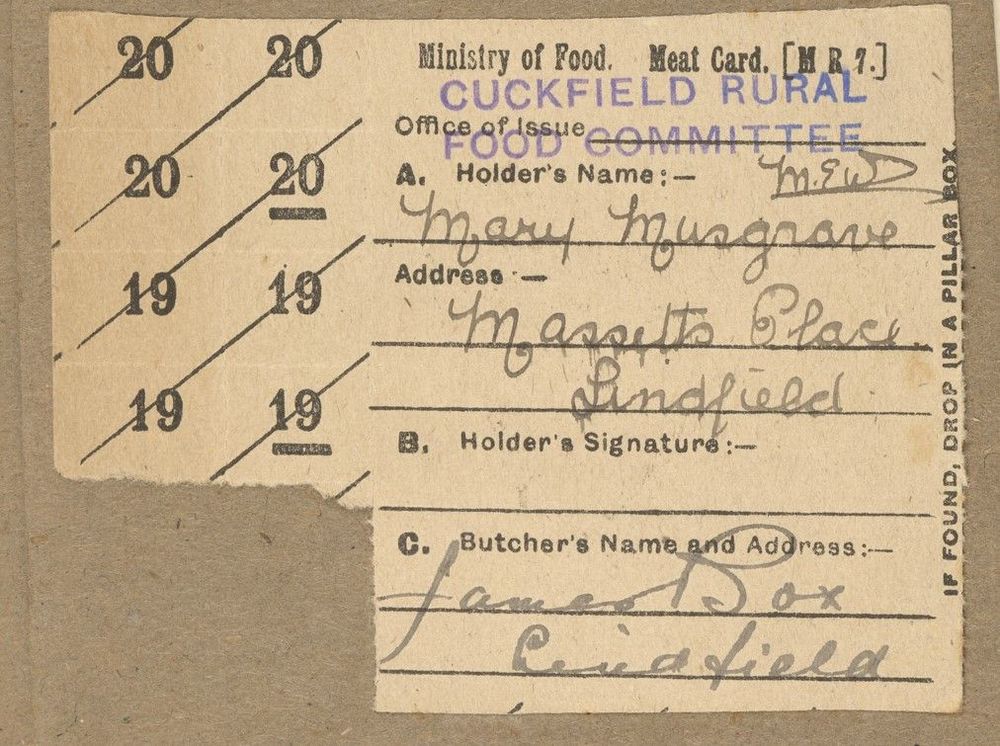

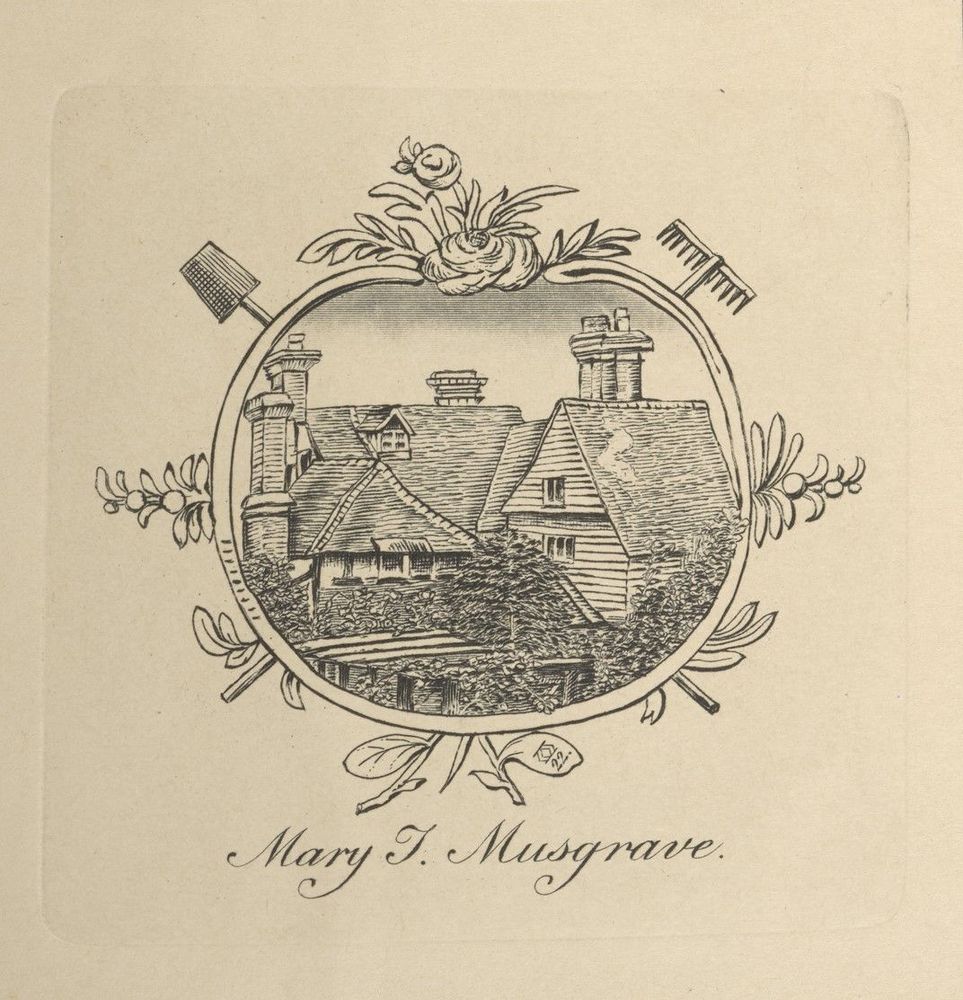

Mary Musgrave's bookplate (a label used to show ownership of a book), designed by Frances Garnet Wolseley. This view can also be seen in a painting by Wolseley (see below). Source: Brighton & Hove Libraries

An unlikely queer icon

After her mother died in 1920, Frances was shocked to find out she had been almost completely left out of her will.

Louisa Wolseley had inherited about £55,000 from her husband's estate, which is more than £2 million today. However, she chose not to leave this money to her daughter. Instead, Frances only received a small annuity, meaning she got a modest amount of money each year.

Her friend Mary Lawrence, trying to comfort Frances, wrote in a letter: "I can only suppose that your mother’s mind was warped beyond recovery."

By this time, the Viscountess was living with the companion she would spend the rest of her life with: Mary 'Mollie' Musgrave.

The wife of a Captain in the Army, Mary moved with Frances to Massetts Place, Sussex in 1918. There they cultivated gardens and bred dogs.

Frances was very fond of this house. There are paintings she made of it in the Hove Library collection, showing that art was another skill she enjoyed. She also designed a bookplate for Mary, which included their home and garden tools in the design.

Later they would move to the village of Ardingly, West Sussex, where Frances lived until her death in 1936, aged 64.

Letters show that Captain Peete Musgrave, Mary Musgrave's husband, knew his wife was living with the Viscountess.

He seemed comfortable with the arrangement. But it's not clear whether he had any feelings or suspicions around the likely nature of their relationship.

Books written by

Frances Garnet Wolseley

In the course of her career Frances Wolseley published several books, covering horticulture, garden design and the county of Sussex, where she lived for much of her life.