From horseback to Big Top:

The early days of circus

19th century circus posters from the Cryer Collection. Left: Cooke's Circus featuring Mr. Kite; Centre: Pablo Fanque's Circus featuring a performance of Mazeppa; Right: One of John Cryer's many scrapbooks. Source: Wakefield Libraries, photos by LibraryOn

Libraries help us access fascinating material about the early years of circus — including rare 180 year-old posters, available to explore online for the first time.

Have you ever wondered where, why and how the circus began?

Circus began as entertainment, but over decades and centuries became an artform.

Its early years contained fascinating characters and stories. The comedy of the ring would often contrast with real-life tragedy.

On this page you'll be able explore previously unseen circus posters from the 1840s, thanks to Wakefield Libraries. They're an example of how libraries can bring local and national history to life for everyone.

Where the circus started

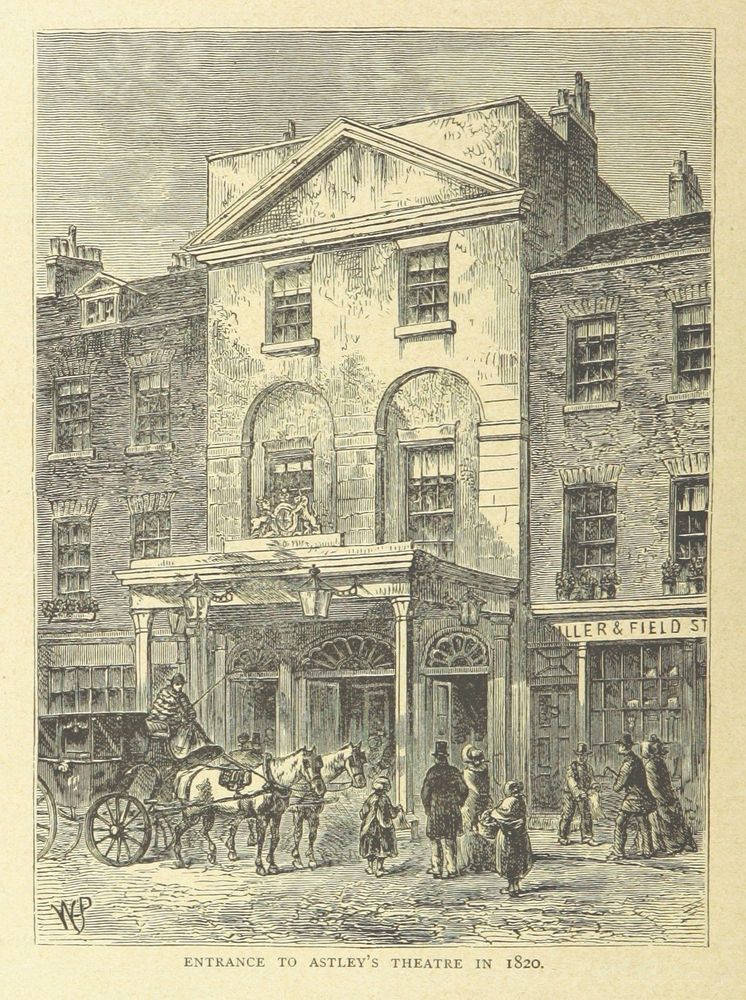

Philip Astley, a former sergeant major, is widely thought of as the father of the modern circus. He was born in 1742 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire.

A lover of horses from an early age, he joined Colonel Eliott's Light Horse regiment (also known as the 15th Light Dragoons) at the age of 17. By the time he ended his service he had developed advanced trick horse-riding skills.

In 1768 he headed to London and set up a riding school on land where, today, you’ll find Waterloo train station. Here he demonstrated his tricks, such as standing on a horse’s back, dismounting and remounting, and standing on his head – all while his horse cantered round in a circle. His wife, Patty, was also a trick rider and performed alongside him.

From outdoor to amphitheatre

In refining his company's tricks, Astley set the size of the circle as 42 feet in diameter. These dimensions are still used as the standard circus ring size today.

Eventually Astley progressed from his open-air riding school and opened an amphitheatre for his shows.

In fact, he ended up having to build several venues in London alone, as they kept burning down – possibly due to the number of candles used to light the space.

Today, if you visit the garden at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, you’ll find a plaque commemorating Philip Astley’s amphitheatre, which stood nearby.

More acts added

To his own daring equestrianism, Astley eventually added other acts to his shows. These included jugglers, tightrope walkers and, in 1770, a clown known as ‘Mr Merryman’.

Astley also added his son, John, as a performer. Similarly skilled on horseback, he would go on to perform for Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France, in 1783. He would have been just 15 years old.

Astley junior’s performance left such an impression on the monarch that it helped his father gain permission to open an amphitheatre in Paris.

However, the French Revolution of 1789 led him to return to Britain, where he found competition from other circuses entertaining the masses...

The importance of marketing

Increased competition meant that, as the 19th century dawned, circuses needed to put increased effort into marketing themselves.

A touring company would arrive at a new place and need to whip up enthusiasm for its limited number of shows before heading off on the road again.

To get the attention of potential audiences, circuses started getting handbills and posters printed. These would be handed out and pasted to walls throughout towns.

The paper used to print these materials would be finer than what we see newspapers printed on today. Advertising specific performances on specific dates, these 'bills' weren't intended to last long.

Even so, one Wakefield bookseller and stationer found them interesting enough to keep. His name was John Cryer.

John Cryer collected handbills, flyers, pamphlets and other ephemera in Wakefield in the 1800s. There was enough material to fill dozens of scrapbooks.

These scrapbooks are now part of Wakefield Libraries’ Cryer Collection, which offers a fascinating glimpse into life in the town in the 19th century.

The printers of these disposable artefacts would surely be very surprised to hear they’re still around over a century later...

Explore 180 year-old circus posters

These 19th century circus posters, part of The Cryer Collection, have been preserved by Wakefield Libraries. They have been digitised here for the first time in collaboration with LibraryOn.

They come from two prominent 19th century circuses: Cooke’s Circus and Pablo Fanque’s Circus, both of which visited Wakefield many times.

From grand 'horse operas' to daring 'bottle equilibrists', from feats of strength to astonishing acrobatics: we invite you to explore the 19th century circus.

Which act do you wish you could have seen?

What the early circus looked and smelled like

This excerpt from ‘Beneath the Big Top: A Social History of the Circus in Britain’, by Dr. Steve Ward, captures the sensations early circus audiences could expect:

An enormous glittering chandelier, lit by hundreds of candles, is suspended above the circular ring and casts a warm glow on the proceedings. The first thing you notice is the smell – of burning tallow candles, of the sawdust in the ring, the odor of horses and the stink of the crowd packed tightly together.

... The people in the upper gallery must have a marvelous view of that chandelier for the entry price of one shilling! It is hot up there and the heat from the candles and the crowd below gathers beneath the roof.

The orchestra is seated between the front of the stage and the ring and are playing a merry tune. In the ring at this moment is a young woman astride three white horses. As they gallop in a circle she balances on one leg on the middle horse and her diaphanous costume billows out behind her. The clown in the middle of the ring laughs and claps.

Light relief in dark times

When circuses first became popular, most audiences would have had few comparable experiences. Travel was only for the very wealthy. What little leisure time people got would have been restricted to the area where they lived.

Moreover, the general quality of life was poor by today’s standards. People were barely expected to live past the age of 40. Many didn’t even live that long, due to disease, poor living conditions and limited medical care.

So a visit to the circus was a chance to leave behind daily worries and be entertained by dazzling feats. When menageries started to merge with circuses, exotic animals added yet more excitement.

Reading recommendations from

Wakefield Libraries' Circus Doctor

Wakefield Libraries engaged the help of Dr. Steve Ward to assess the significance of the Cryer Collection's circus bills. Here he recommends further reading for anyone interested in learning more about the history of circus.

A dangerous profession – and spectacle

Circus owners didn’t generally prioritise the safety of performers, workers and spectators. With animals, daring feats and temporary structures in the same space, there was a lot that could go wrong.

Here are just a few examples of times when tragedy struck.

Image courtesy of Norfolk County Council Library and Information Service

In May 1845 Cooke's Circus advertised that Mr. Nelson the clown, sitting in a tub, would be pulled along Yarmouth's River Bure by four geese.

Hundreds of people gathered on a bridge to watch. The bridge collapsed, causing the deaths of 79 people - many of them children. The bridge was later assessed to have substandard welding that contributed to its collapse.

Nobody was held criminally responsible for the deaths. Today a memorial marks the site of the tragedy.

Circus history - more resources

Sources

Partners

Thanks to Wakefield Libraries, part of Wakefield Council, for preserving the materials that help stories like these to be told. Thanks also to Dr. Steve Ward for his expertise and permission to include an excerpt from his book 'Beneath the Big Top: A Social History of the Circus in Britain’.